The Capybara Sundial

Field report, remembrance, chronicle, prophecy

They stood in their mute encirclement of the old stone dial whose gnomon cut the sky like some blade buried to the hilt, watchful and unknowing in the ruin of that bloodred firmament where the last clouds moved like smoke over a charred plain and the trees stood stripped and dead, each branch a black hieroglyph inscribed upon the horizon of a world that had outlived its own design, the beasts patient and stolid as though they had always been there and would remain long after the monument had crumbled to dust, their vigil primal and inexplicable, witnesses to some covenant made before memory, before time itself had learned to mark its passing on the sundial face of that strange pillar.

In the ochre waste where the ruins stood skeletal against a sky the color of old brass the wheel leaned there canted in the sand, its compartments cut like cells in some vast and intricate honeycomb, and in each cell the figures stood or knelt or embraced in attitudes of supplication or coupling or murder—who could say which—their forms worn smooth as creek stones, anonymous, the wheel itself a mandala of flesh repeated, and at its center the alien regard, that hairless and implacable witness with its eyes like pits bored into nothing, and behind it the larger figure risen up out of the sand itself perhaps or simply waiting there since the world’s morning, its skull face turned toward some horizon that had long since ceased to exist, the whole tableau composed in that desolate light as if arranged by hands that understood geometry but not mercy, the aqueducts in the distance marching toward their own extinction, and over it all the sky churning with ancient poisons, and you got the sense looking at it that the wheel had turned and would turn again, grinding through its permutations of torment or ecstasy—no difference finally—each figure locked in its chamber like a sin in the heart, inexpiable, the math of it precise as death, the alien at the hub serene in its witnessing, and all of it half-buried in that sterile dust which was maybe the dust of empires or of worlds or just dust and nothing more, the wind beginning to cover it over grain by grain in the measureless noon.

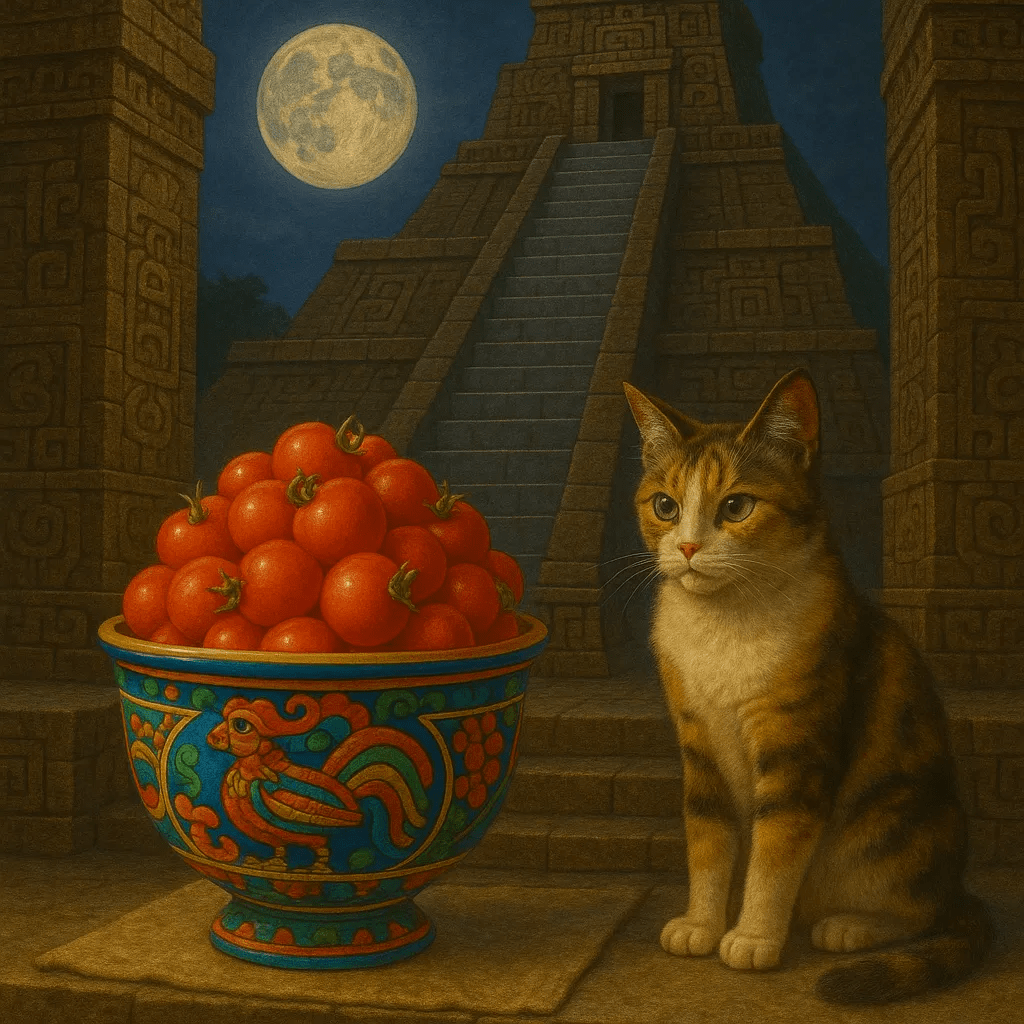

In the days when the pyramids still remembered the names of their builders and the moon hung low enough to taste the smoke of copal fires, there lived in the city of forgotten gods a calico cat who had been appointed by no one in particular to guard a bowl of tomatoes so red they seemed to contain all the sunsets that had ever bled across the valley, and the bowl itself was painted with serpents whose scales were the colors of paradise before the fall, and the cat whose eyes held the green of jungles that no longer existed would sit there every night without fail, not because anyone had asked her to or because she expected payment in fish or cream, but because her great-great-grandmother had whispered to her great-grandmother in the language that cats spoke before they forgot how to speak that the tomatoes were not tomatoes at all but the crystallized tears of the last priest who had climbed those steps behind her, one hundred and seven years ago, carrying his own heart in his hands as an offering, and that whoever ate them would remember everything—every love, every betrayal, every small mercy and large cruelty since the world began—and would go mad from the weight of it, and so the calico sat there in the moonlight which was itself a kind of memory, patient as stone, her whiskers trembling slightly in the night wind that carried rumors of rain that would not fall for another three hundred years, and the tourists who sometimes stumbled into that courtyard would photograph her and say how charming, how picturesque, never knowing they were looking at the last guardian of a sorrow too beautiful to be consumed.

The cat regarded him across the rust-colored waste with eyes like amber coins struck in some ancient forge. Behind them the ringed planet hung enormous in the darkling sky, a judge presiding over dominions of dust. The creature beside him stood in its alien perpendicularity, eyestalks searching the horizon for what sustenance this world might yield or what communion might be drawn from the silence.

They were pilgrims both in a land that knew no scripture. The cat’s fur held the darkness of collapsed stars and its red collar was the only covenant between the world it had known and this one. The companion creature, orange as oxidized iron, as the very soil beneath them, seemed born of this place, extruded from the planet’s own weird geometry.

What word could pass between such beings? What language obtains in the transit between one world and another? They sat in that vast cathedral of emptiness and the wind if there was wind carried no answer. Only the patient mathematics of orbit and decay, the supreme indifference of the cosmos to the small and the breathing, the furred and the strange, all that moves and must one day cease to move upon the surface of ten trillion worlds or one.

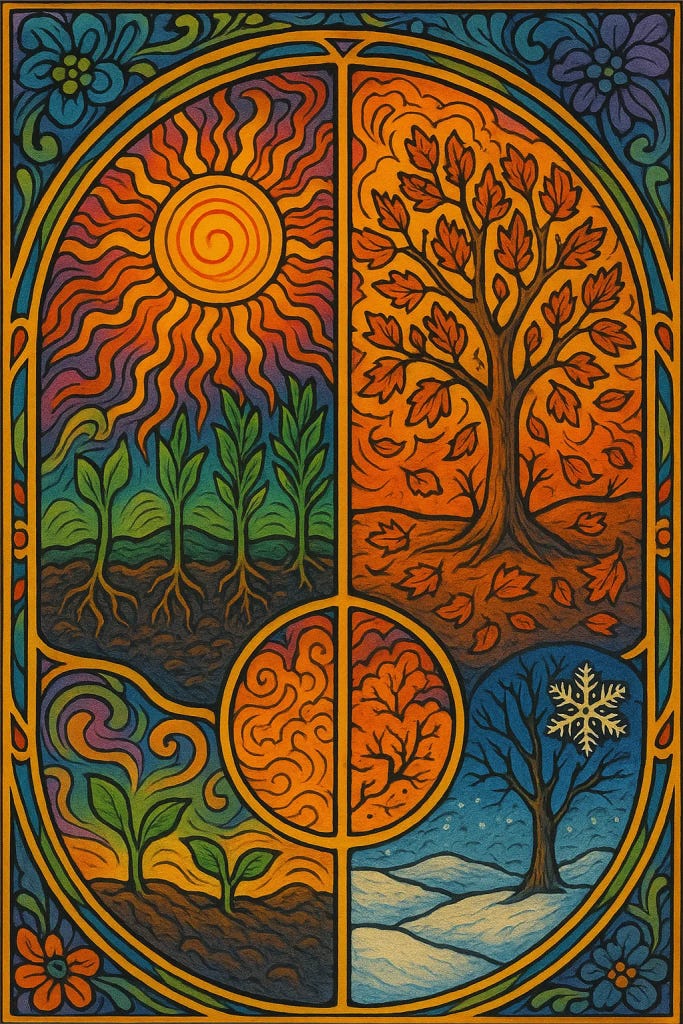

The composition, with its quadrants of sun, sprout, leaf and snowflake, presents itself less as a picture to be grasped outright than as a delicate arrangement of suggestions—each season leaning into the next with a sort of half-withheld confidence, so that one’s apprehension of the whole is not a matter of stark recognition but of slowly succumbing to the impression of something at once inevitable and elusive, intimate and remote. The solemn sun lingers above roots that, in their patient secrecy, foretell the tree’s splendor and decline, while autumn’s golden flames already whisper to winter’s pale breath, all encircled by a border of ornamental arabesques that seem less decoration than the very pulse of time itself.

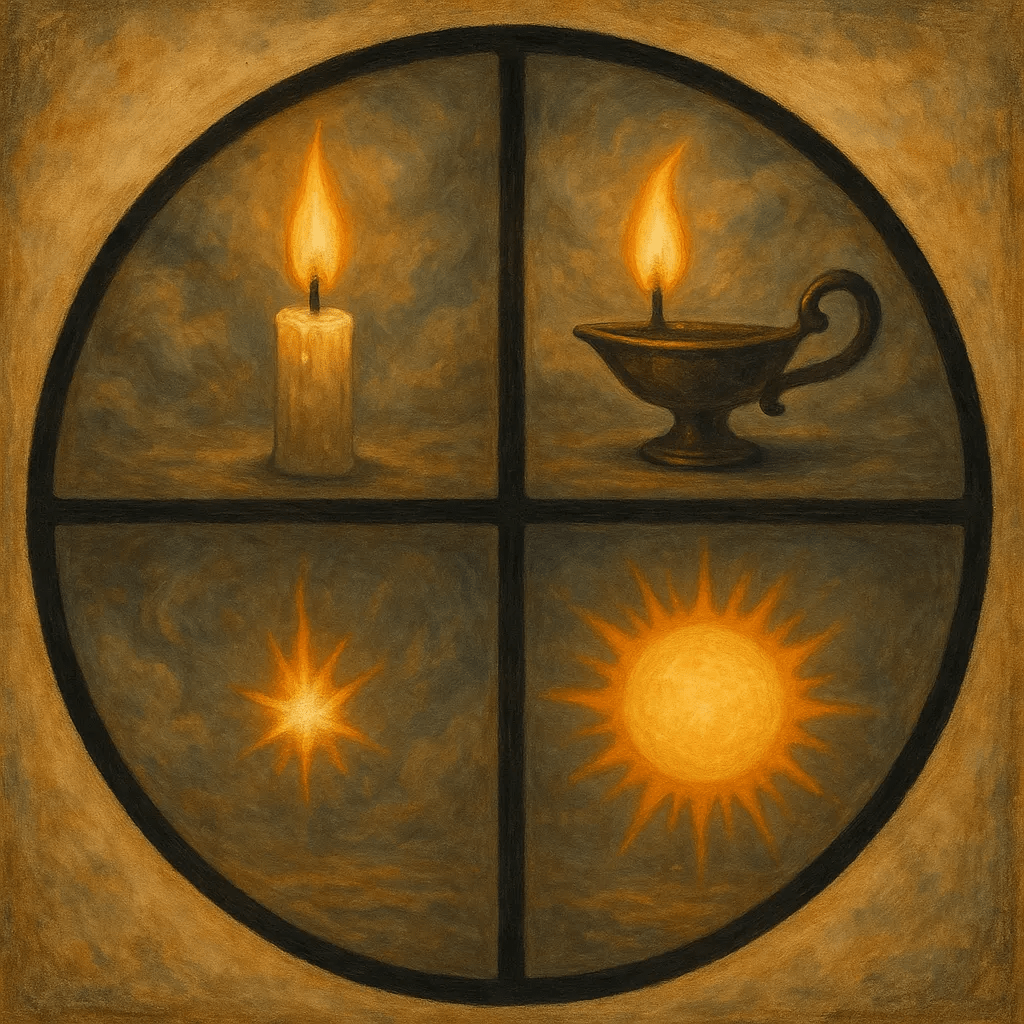

In that circular tableau where four luminosities—the modest taper whose flame trembles with the same hesitant grace as the consciousness of a child taking its first uncertain steps toward self-awareness, the oil lamp’s more refined radiance (suggesting perhaps the soul’s passage through civilizations of increasing sophistication, from the crude rushlight of primitive epochs to the elegant vessels of a more cultivated age), then that sharp stellar burst resembling nothing so much as the sudden, piercing moment when one apprehends, in the midst of life’s mundane progression, a truth previously obscured by habit’s comfortable veil, and finally the sun itself in all its pneumatic fullness, that orb which seems to contain within its swollen circumference all the accumulated experience of previous existences now ripened into a wisdom warm and all-encompassing—illuminate their separate chambers yet remain forever divided by those implacable black bars which suggest that even as the soul ascends through its successive incarnations, each life remains enclosed within its own inviolable moment, touching yet never quite merging with those that came before or shall come after, much as the various epochs of one’s own existence, though linked by the continuous thread of memory, retain each its distinct and unrepeatable savor.

The cats sat upon Andy narwhal in the crystalline dark, their caps the colors of some merchant caravan out of antiquity, rainbow-banded like Joseph’s coat. Above them the auroral light moved in great sheets across the firmament, green and luminous, a celestial fire that burned without consuming. The beast beneath them cleaved through black waters, its horn a pale tusk jutting forward like the spear of some drowned knight errant.

The orange cat’s eyes held the simple faith of all creatures who know not their fate. The black cat watched with an older knowing. They rode the leviathan through that polar waste beneath skies no different than those which men had watched since the world was made, wondering at their brief passage through the dark and whether any hand had set the stars or whether the stars themselves were but another kind of wanderer, alone and purposeless in the void.

The water rolled away from the narwhal’s passage in folds of deepest cobalt. What lay beneath no man could say. What lay ahead the same. And still they rode.

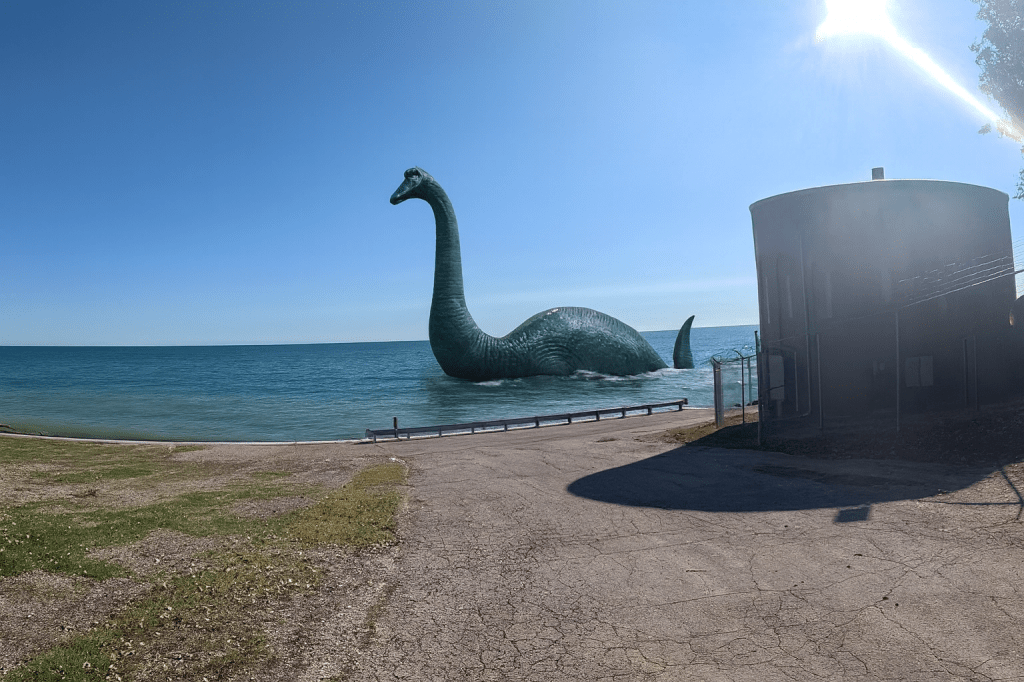

Dippy the Diplodocus rose from the deeps like some antediluvian dream made manifest, its great columned neck ascending from the gray waters of Lake Michigan. The Cudahy pumphouse stood witness, that cylinder of concrete like some monument to the age of steel and diesel, now dwarfed by this visitor from an age when the earth itself was young and the sun burned with a different fire.

The path lay cracked and weatherworn. The grass at its margins yellowed and sparse. No sound but the lapping of water against the shore and the distant cry of gulls wheeling in that depthless blue. The creature regarded the land with eyes that had seen the world when it was green and savage, when great ferns covered the earth and the only law was hunger and the brutal mathematics of survival.

It had returned as if drawn by some lodestone buried deep in the memory of stone and water, as if the pumphouse itself had called to it across the millennia, one testament to existence calling another. The shadow it cast stretched long across the path and the people came or they did not and the lake went on in its turning and the earth turned beneath it, indifferent as always to the affairs of men and monsters alike.

They drove through the country of dust and ruin, a place where the sun burned down like judgment, the sky above them vast and pitiless. The Cadillac, blue as a forgotten dream, cut along the blacktop, humming low like some hymn. Two cats sat within it, one black as the pit and the other tawny and watchful, the driver. Their eyes narrowed not with worry but with the cold calculation of those who had seen the world and found it wanting.

They passed saguaros like sentinels thorned and skeletal, reaching for a heaven that did not answer. The land stretched on, empty save for the wind, which bore no scent of life, only the stale breath of things long dead. The cats did not speak. Something had been left behind. Or waited ahead. Either way, the car moved forward, indifferent. They drove on.

The temple rose from dark waters like some monument to gods long turned to dust. The lunar disk hung in that firmament pale and absolute, a cyclopean eye bearing witness to the earth’s old corruptions. Rain fell slantwise through the darkness and the statues stood in their weathered vigil, their faces worn smooth by centuries of wind and grief.

The door at the summit, that blue anomaly, some absurd portal grafted onto antiquity as if modernity itself were but another stone to be laid upon the altar of ruin, testament to all seekers who’d climbed before and found at the top only what they’d carried with them all along.

The sea moved in its ancient rhythms, indifferent, immutable. The rain fell. The moon watched. And the door, that incongruous blue door, stood closed against the supplicant and the pilgrim alike, offering neither entrance nor explanation, only the cold comfort of its own inscrutable existence in a world where all answers are bought with the same coin and all climbers arrive at last to the same locked threshold.